It’s time for a new adventure.

I’m leaving AWS and joining Nebius, one of the top AI clouds, as their Head of Physical AI.

I’m also leaving my first professional love — spatial computing. At least in its most direct and advertised form, i.e. AR, VR, 3D, aka ‘XR’.

But in another sense, I’m not leaving at all. I’m going deeper.

As we’ve discussed, spatial computing is far more than XR. This is just one end-point; just one form of a computer relying on sensors to localize, track, and understand the physical world.

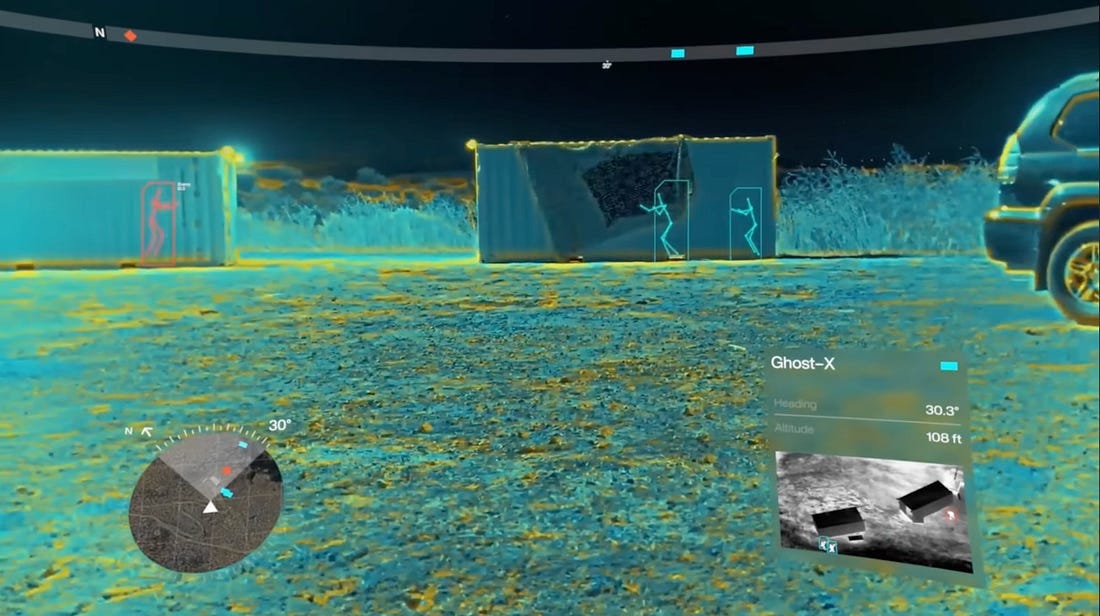

Self-driving cars, mobile robots, humanoids, autonomous drones... these are all ‘spatial computers’, each relying on a similar technical foundation, with similar computer vision tech, simulation tools, and ‘spatial’ data types, e.g. lidar, point clouds, 3D, video, IoT/sensors.

The key difference?

Autonomy and their ability to impact/interact with the physical world.

So again, I’m not leaving. I’m just moving downstream; from a ‘spatial tributary’ to a gushing river, surging with capital, progress, and commercial opportunity.

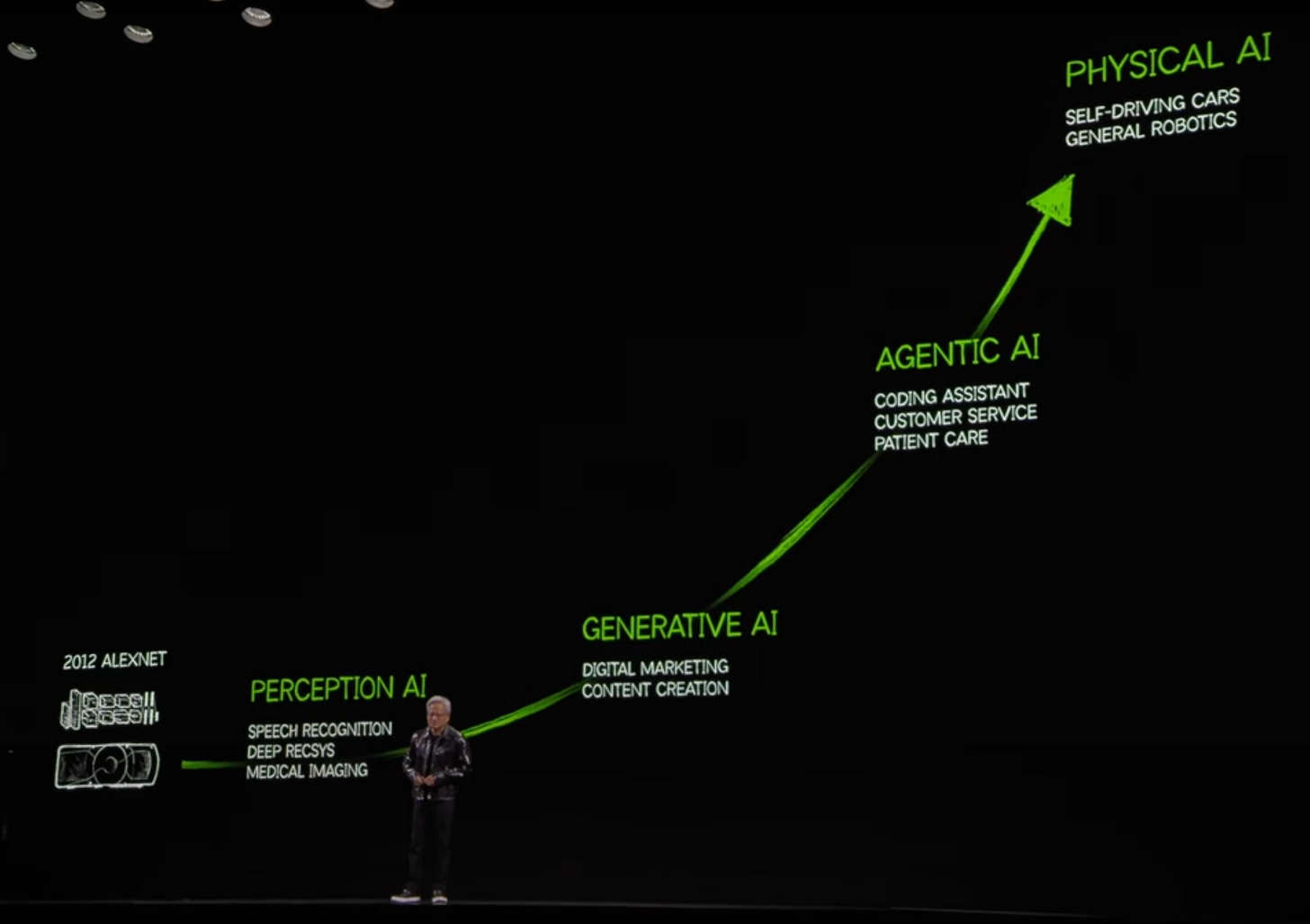

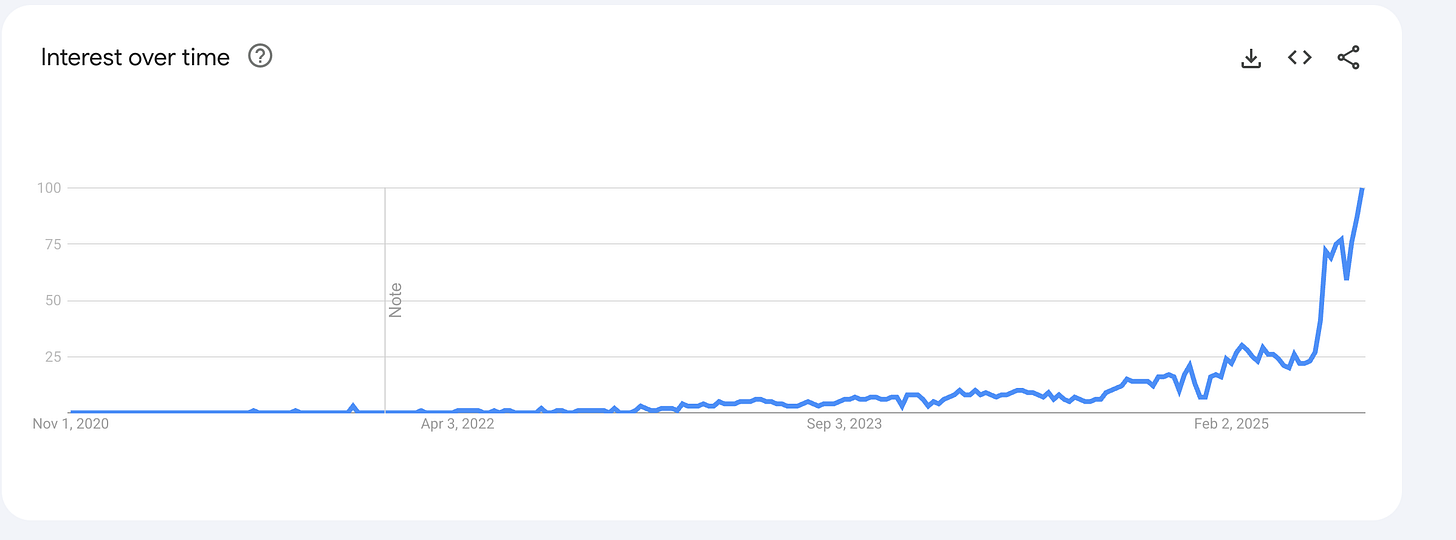

Jensen Huang (NVIDIA’s CEO) popularized the term ‘physical AI’ about a year ago. As it goes… interest and awareness has exploded ever since.

To be sure, Jensen likes to live 10+ years in the future. Physical AI remains early and is in a hype cycle of its own. One that, at first glance, feels like the hype cycle that sucked me into XR (heartbreak and shattered dreams, abound).

But this feels different. The timing feels right.

This essay summarizes why. You’ll leave here with a L200 grasp of this new tech stack and the key innovations worth monitoring.

In Part II of this series, we’ll cover some of the challenges that remain, including the ones that I’ll be trying to solve in my new role at Nebius.

But first, some context.

What exactly is physical AI?

It’s the next (and I believe most impactful) phase of the AI revolution.

Definitions vary, but I like to keep things simple. I define physical AI as computers/machines that can understand, represent, and/or interact with the physical world.

It’s a broad umbrella with common underpinnings; the big three are real-world data, computer vision, and of course, generative AI.

The result doesn’t have to be as complex as a robot. It can include an AI-powered camera on the factory floor, recognizing anomalies and then adjusting an assembly line in real time.

It can also include AR glasses, with cameras gathering front-line insights and providing work instructions, or informing a soldier on the battlefield.

(This is what I’m most exited about — the combo for AR + robotics to keep humans ‘in the loop’, i.e. allowing both humans and machines to see the same thing and work/sing off the same sheet of music)

More abstractly, Physical AI is the merging of the physical and the digital world; the connection of atoms to bits.

Along the way, this includes the purely virtual, in which the physical world is reconstructed & simulated.

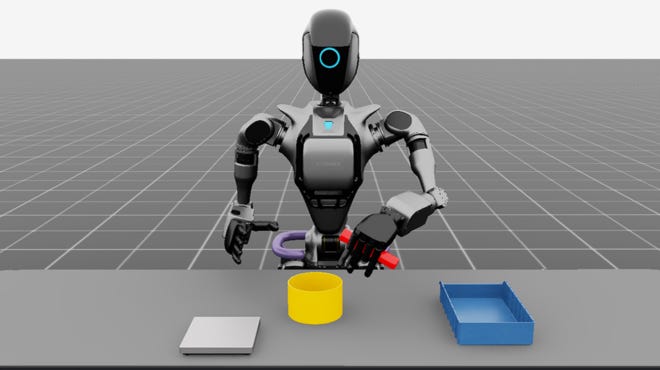

The most exciting examples here are Large World Models like Googles Genie (GenAI that can create virtual worlds with a single prompt) and digital twins: the simulation sandboxes where ‘robots learn to be robots’.

(If you haven’t seen this two minute Genie demo video, stop right now & watch. Trust me)

Most importantly, physical AI holds the key to tech’s ultimate endgame: artificial general intelligence (AGI). That key is the embodiment of AI. Without it, machines will struggle to gain a true understanding of our world, its physics, its randomness, its interconnectedness, our larger role within it all. With physical AI, perhaps the greatest mysteries of the universe will be revealed...

I find it all endlessly exciting and hopeful, and just incredible that we get to experience this phase of human history.

But I digress. Putting my realist cap back on.... We still have a little ways to go.

How much further?

I believe we’re where LLM’s were between 2017 - 2019.

World class teams have been funded, foundation models are in development, compelling demos are sparking the imagination, and VC dollars are flowing.

Most notably, many of the top AI minds from academia are leaving the labs in droves, founding companies and taking the commercial leap (e.g. Chelsea Finn & Sergey Levine @ Physical Intelligence, Ken Goldberg @ Ambi Robotics)

As such, it feels like we’re 3-4 years from the ChatGPT moment and 5-7 years away from this stuff hitting meaningful scale (e.g. robotic manufacturing & supply chains are dialed, millions of units are being deployed in the enterprise, and consumer adoption is starting to ramp).

And this is slightly conservative. After all... humans are terrible at grasping exponential curves.

What exactly is the ChatGPT moment?

It’s when we have a generalizable, foundation model for physical AI. Aka: an API to the real world, that can understand, navigate, and complete general tasks in a ‘zero shot’ fashion. Meaning, it can perform a task it has never been explicitly trained on before.

And when I say generalization, I mean across numerous variables, the most important being hardware. Meaning, it works with not just one form factor, but across many form factors, translating data + context into an action/output on humanoids, quadrupeds, AMRs with four arms, or even AR glasses.

So why now?

Because these foundation models are starting to arrive, giving developers a substrate upon which to further train & fine tune.

The first wave emerged in 2023/24. The most notable being Google’s RT-1 and RT-2, Physical Intelligence’s π0, Covariant’s RFM-1, and NVIDIA’s Project GR00T.

You can liken these to OpenAI’s GPT-1 & 2. Not super useful out of the box, but mind-blowing technical breakthroughs, nonetheless. They’re the result of upstream innovation in three main areas: (1) new architectures, (2) new data regimes, and (3) new training recipes.

(1) New Architectures

You’ve probably heard of the Transformer: the architecture that quietly changed the AI world in 2017. It’s the engine behind ChatGPT, Gemini, and every modern large language model. Transformers work by treating language as a sequence of tokens and predicting what comes next.

Its impact on text was obvious. Its impact on physical movement? Less so.

But roboticists quickly saw the parallel. A robotic action is just another kind of sequence. Instead of words, you have motor commands. Instead of sentences, you have trajectories—reach, grasp, lift, place.

Once we applied Transformers to robotics, something remarkable happened: robots could learn useful skills from dozens of demonstrations instead of thousands. Efficiency jumped by an order of magnitude, and for the first time, robots gained a model that could actually generalize across varied tasks. But moving is only half the battle. To interact with the world, you have to understand it.

This is where the Vision-Language-Action models enter the picture (aka VLAs)

Their predecessor was Vision-Language Models like CLIP. These systems fuse text and imagery into the same conceptual space, teaching machines to recognize “dog” as an idea, not a blob of pixels.

As you probably guessed, VLA’s add the missing piece: action. They “tokenize the world,” weaving together text tokens, image tokens, and motor tokens into a single sequence.

If you give them a high-level instruction like “pick up the apple,” and they can identify the apple, understand the intent, and sketch out a plan. It’s the beginnings of a generalist robotic brain.

But a brain that can imagine a plan is different from a body that can execute it.

For that, the industry started turning to Diffusion Policies. This is the same generative magic behind image creation tools like Midjourney or Nano Banana.

In generative art, diffusion starts with pure noise and gradually “de-noises” it into an image. In robotics, it starts with noisy, meaningless motor twitching and de-noises it into a fluid, coherent motion.

This approach solves one of robotics’ oldest curses: the multimodal problem.

This problem arises in tasks that have more than one ‘answer’. Take opening a drawer for example. It has multiple valid solutions: you can grab the handle from the left, right, or top.

Older models (convolutional neural networks) tried to average these demonstrations and ended up reaching for the center, where no handle exists. With diffusion, it doesn’t average; it chooses. It locks onto a single valid mode — left-grab, right-grab, top-grab — and executes it with a kind of crisp, biological confidence.

In short, this gives robots the decisive body that matches the VLA’s semantic brain.

The result is a dual-system architecture. One that looks/feels a lot like human mind, with System 1 and System 2 modes of thinking. And yes, it’s very similar to the concept you’ve probably heard from the book Thinking, Fast and Slow, by Daniel Kahneman’

System 1 (the body) is the the ‘fast’ diffusion policy. It’s reactive, and precise. It takes a strategy and turns it into the 50-millisecond motor adjustments needed to actually grasp a crinkled wrapper.

Systems 2 is the ‘slow’ brain, powered by VLA. It’s deliberate and semantic. It looks at the room, understands “I need to clean up that trash,” and generates the high-level strategy.

But even with this powerful combo, the robot is still just mimicking. It doesn’t truly know if it succeeded. To get closer to human-like intelligence, you need a closed loop system that can learn from its mistakes and upgrade itself on the fly (we’ll cover this further in Part II).

(2) New Data Regimes

Okay, so we now have this dual-system architecture, giving us the right ‘engine design’ for physical AI. Next we need fuel, aka data.

In the purely digital world of LLMs, fueling AI is relatively easy. You scrape the entire internet — billions of images, trillions of tokens of text — and feed it into a GPU cluster running frameworks like PyTorch or JAX.

But in the physical world, there is no internet to scrape. You can’t just download “how to fold a shirt” or “how to solder a circuit board”. You have to create it (although, heavy research is underway towards making YouTube videos digestible for robotics).

This is currently the single biggest bottleneck in Physical AI.

To solve it, the industry has made exciting progress in three key areas: data-crowdsourcing (The Community Pot), teleoperation at-scale, (The Grind), and simulation (The Infinite Well).

The Community Pot: Open X-Embodiment

For years, robotics was a fragmented discipline. A lab at Stanford would collect data for a Franka Emika arm and a lab at MIT would collect data for a Kuka arm. But the data was siloed, incompatible, and useless to anyone else.

That changed with the Open X-Embodiment Collaboration.

Think of this as the “ImageNet moment” for robotics. Led by Google DeepMind and 20+ other institutions, this project pooled data from 22 different robot types into a massive, standardized dataset.

The hypothesis was simple but powerful: positive transfer. They bet that a robot arm in California could learn better grip strategies by studying the data of a completely different robot arm in Zurich.

And they were right. Models trained on this collective “community pot” of data outperformed those trained on narrow, proprietary datasets. It proved that if we stop hoarding data and start standardizing it, we can bootstrap general intelligence much faster.

The Grind: Teleoperation Fleets

Community data is great for general skills, but for high-precision tasks, you need the “gold standard” data, aka human intuition captured at 50Hz.

Enter teleoperation fleets.

If you walk into the offices of the top Physical AI startups today, you won’t just see engineers coding. You’ll see rows of operators wearing VR headsets or using haptic controllers, “puppeteering” robots to do chores, assemble parts, or sort logistics.

This is the grind. It’s painfully slow and expensive (1 hour of human time = 1 hour of robot data). But it is currently the only way to capture the subtle “English” a human puts on a screwdriver, or the way we instinctively jiggle a key to make it turn. This data creates the kernel of knowledge that models need to imitate.

Fortunately, we now have a wave of companies like Scale AI, Sensei, and Deta who are industrialization this capability, standing up “Data Engines-as-a-Service” to collect thousands of hours of expert demonstrations.

Helpful and promising... but its not enough.

The Shortcut: UMI

To ease the TeleOp grind, a promising new idea surfaced back in 2024. It’s called Universal Manipulation Interfaces (UMI).

Instead of teleoperating a specific robot through complex rigs, UMI flips the model. Humans manipulate the world directly using a lightweight, handheld gripper with a wrist-mounted camera.

This captures rich, first-person visual and motion data—how objects move, how forces are applied, how tasks unfold in real environments—without requiring a robot in the loop at all. In effect, it decouples data collection from robot hardware, turning natural human interaction into training data.

The real unlock is generalization. Because UMI represents actions in a relative, hardware-agnostic way, these demonstrations can be transferred across different robot arms, grippers, and platforms with minimal retraining.

It doesn’t replace teleoperation fleets or simulation, but it meaningfully expands the funnel; lowering cost, increasing diversity, and capturing human intuition at scale.

If teleoperation is the gold standard and simulation is the infinite well, UMI sits in between: a faster, more portable way to turn human skill into robot competence.

The Infinite Well: Solving Sim-to-Real

While teleoperation and UMI capture quality, they both have a hard limit: human time.

You can’t hire a billion humans to teach a billion robots. Eventually, the robots must learn in the virtual world. Especially if we want to capture all the edge cases and complexity of the real world.

This is the promise of what the industry calls ‘Sim-to-Real’ (aka learn in simulation and transfer a policy to reality)

In the past, simulators were essentially video games with bad physics. If a robot learned to walk in code, it would often fall over the second it stepped into the real world because the friction was slightly off or the lighting was different.

The industry has started to solve this with a technique called ‘domain randomization’.

Think of this as the “brute force” approach. Since you can’t match reality perfectly, you just randomized everything, creating chaos across every possible dimension; lighting, floor lay outs, friction levels, temperature, sensor noise, etc.

The ideas is that if a robot can survive the chaos, the real world will feel easy by comparison.

This works to an extent, but it’s inefficient, lacks complete accuracy, and leaves ‘reality’ gaps.

But those gaps are starting to close. Three new technologies are maturing that can hep us clone reality rather than just guess it.

The first is neural rendering (aka gaussian splatting).

Traditionally, building a simulation meant hiring 3D artists to hand-draw every table, screw, and factory wall. This is slow, expensive, and rarely 1:1 with reality.

Gaussian splatting flips the script. It allows us to walk through a factory with a camera, scan the environment, and “splat” a photorealistic digital copy into the simulator. It captures the messiness of the real world: the rust on the metal, the grease on the floor, the weird reflection on the window. This matters because robots are easily confused by visual noise.

Now, they can train on the exact visual chaos they will see on deployment day.

Next we have ‘Differentiable Physics’ within the simulations. Old simulators were “black boxes.” If a robot tried to pick up a cup and failed, the simulator effectively just said, “You failed.” It didn’t explain why.

The robot had to guess randomly to fix it.

Differentiable simulators (like those powering NVIDIA’s Isaac Lab) are “glass boxes.” They provide mathematical gradients. Instead of just saying “Fail,” the simulator says, “You failed because your grip force was 10% too low for this friction coefficient.”

It gives the AI a roadmap to the correct solution, speeding up the learning process exponentially.

With better sim tools in hand, the next breakthrough is “Real-to-Sim-to-Real Loops”, allowing developers to fine-tune the virtual world to match the real world 1:1.

To do so, developers deploy the robot in the real world and wait for it to mess up.

When it fails, they take that log data and feed it back into the simulator to auto-tune the physics until the simulation perfectly matches the failure they just saw. So we aren’t just simulating the world anymore; we are calibrating a ‘physics accurate’ digital twin in real-time.

Now, imagine what happens when we combine these “digital twins” with Generative World Models (like NVIDIA Cosmos or Google’s Genie), which let us generate entirely new 3D training environments from a simple text prompt.

This will be the take off point, moving us from a world where data is scarce to a world where the only limits are the amount of compute we can throw at the simulation.

(3) New Training Recipes

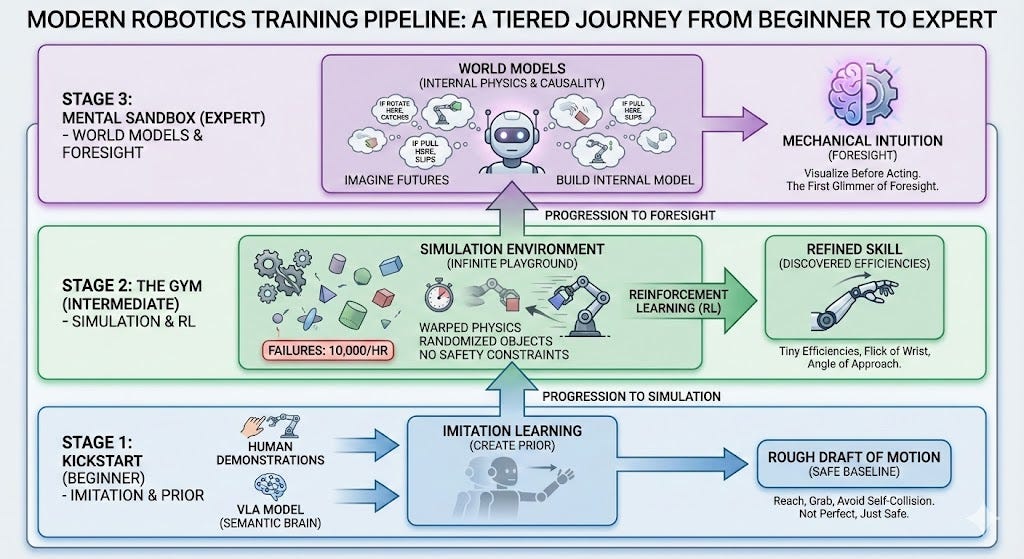

We now have the right blue print and we’re starting to get more data. The final answer to ‘why now’ is all new training recipes, yielding pipelines that look more like a staged learning curriculum than just a single ‘lesson’.

For most of robotics history, you had to choose between two flawed religions: imitation learning (IL) or reinforcement learning (RL)

IL is the “monkey see, monkey do” doctrine. You’d teleoperate a robot through a task a thousand times, and it would replay a fuzzy statistical version of your motions. This has been safe and predictable, but it only scales linearly with human time/effort.

RL is the faith of trial and error. You give a robot a goal, a reward score, and then let it stumble through the problem until it figures out the rules. This is how AlphaGo shocked the world.

But in robotics, “trial and error” isn’t theoretical. It’s metal slamming into metal; motors burning out, drones flying into walls. And as mentioned, simulation doesn’t yet cover every edge case. It’s also just really hard for most teams to do well (requires a unique combo of dev talent across infra, sim tools, 3D dev, etc).

Historically, the industry was stuck between these two extremes. Today, that dichotomy has dissolved. The frontier isn’t about choosing one religion over the other. It’s about stacking every ingredient—imitation, RL, prediction, simulation—into multi-stage pipeline that take a robot from novice to expert.

Two distinct philosophies have emerged from this blending. Both are producing breakthroughs, but along very different paths.

Path 1: Simulation-Heavy

The first path — championed by Google, DeepMind, TRI, and NVIDIA — leans heavily on simulation and RL.

You start with a pre-trained foundation model (usually a VLA) that already understands objects, scenes, and basic motions.

You then add a small number of human demonstrations to shape this knowledge into a safe behavioral prior, aka a rough draft that keeps the robot from flailing.

With this baseline in place, the robot enters the simulator, i.e the “infinite gym.”

In sim, physics can be bent, lighting randomized, textures swapped, and time accelerated. Failure costs nothing. This is where RL thrives: thousands of attempts per hour refine the rough draft into polished skill, uncovering tiny efficiencies no human ever thinks to demonstrate.

Recent advances add one more layer: foresight. Instead of reacting frame-by-frame like a goldfish, World Models are starting to give robots an internal physics engine, letting them imagine how an action will unfold before committing to it; predicting slips, collisions, or ideal grasp points. Much like an athlete visualizing a race, the robot rehearses futures and picks the best one.

Put it all together, you get a system that understands, refines, and anticipates. But not everyone believes simulation is the best approach…

Path 2: The Real-World-First Curriculum

While simulation is powerful, it’s also expensive, brittle, and often suffers from the “sim-to-real” gap.

In response, companies like Physical Intelligence, Skild AI,, and 1X are proving that you can achieve general-purpose manipulation without heavy RL or sim. That is… if you have enough real-world data.

Similar to the simulation path, this journey begins with a Pretrained World Encoder. Whether it is a Vision-Language Model like CLIP or a VLA like π₀ (Pi-Zero), this gives the robot conceptual understanding before it ever sees a teleoperation demo.

The divergence happens next.

While sim-first teams rely on RL to discover skills, real-world teams bet on Massive Supervised Imitation. This isn’t just a few dozen demos. This is brute force at scale. Physical Intelligence utilizes ~50,000 teleop demos; Covariant leverages millions of manipulation attempts. This creates a massive prior: a raw instinct for how humans interact with the world.

From there, the accelerator is Self-Supervised Learning.

These companies treat every single frame of robot data (i.e. logs) as a lesson, mining camera video, gripper-camera views, failed grasps, and even passive background motion, all teaching the robot physics and causality without needing an explicit reward function.

Finally, once deployed, they use online adaptation, aka ‘learning on the job’ by tweaking the robots tactics in real-time based on sensor feedback. This allows them to handle slips, nudges, and new objects without needing a full RL training loop

Two Paths, One Destination

Despite their difference, both paths are converging toward the same ideal: machines that understand their environment, learn from experience, imagine the future, and refine themselves over time.

The future will likely blend the two. Either way, we are no longer teaching robots to copy us. We are teaching them to learn from us, practice without us, and ultimately, surpass us.

The Final Bottleneck

We’ve covered the brains (VLA), the bodies (diffusion), the fuel (data), and the training recipes (hybrid pipelines).

On paper, this is the formula for Physical AI, and after decades of tinkering, robotics is at an inflection point. But there is a final, unsexy truth standing in the way…

The bottleneck is no longer hardware. It’s not sensors, actuators, or even algorithms.

The bottleneck is infrastructure.

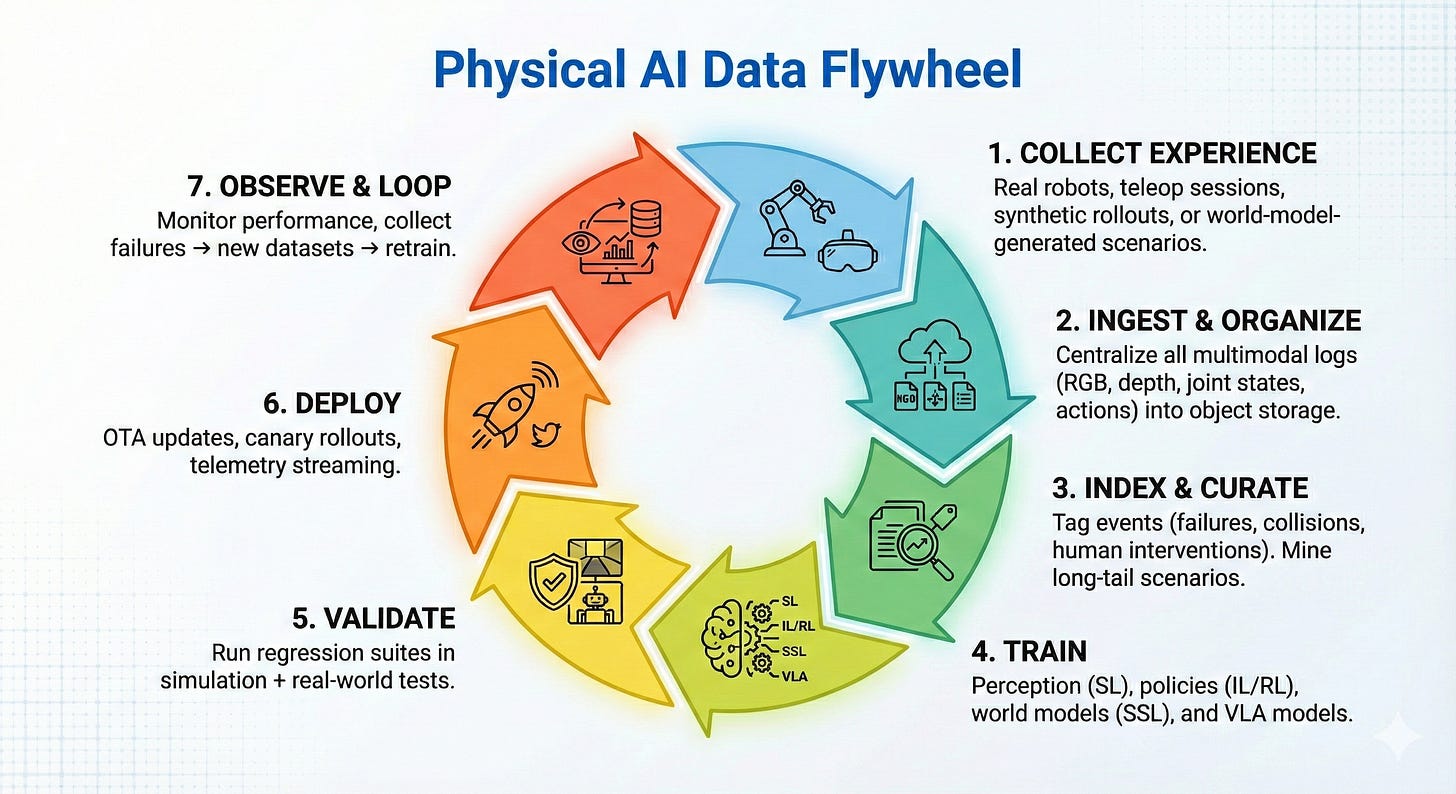

Robotics companies are all trying to do the same thing: build systems that learn from experience, improve with data, and become more capable with every iteration. But the workflow is fundamentally broken.

If you spend a week inside any robotics organization (humanoid, warehouse AMR, manipulator, or AV), you’ll see the same story: a bunch of engineers — some of the brightest minds in AI — spending 80% of their time fighting the cloud rather than solving robotics.

They’re building bespoke infrastructure from scratch, consistently reinventing the wheel, and often stuck in DevOps hell.

What they want instead is a fully automated robotics data flywheel — a system where robot logs ingest themselves, simulators spin up on demand, training datasets auto-curate, training pipelines retrigger on new edge cases, and updated models roll out safely across the fleet.

This is the problem space we’ll explore in Part II. Until then, enjoy these robot bloopers — a great reminder that until we can operate data fly wheels with ease, this is the extent of most robot careers: extremely expensive slapstick comedians.

great article. very informative

Great Article. Thanks!