Future-Proofing Your Self: A Survival Guide for the Age of AI | Part I

The illusion of self and why it matters now

This essay series explores one of humanity's greatest mysteries: the illusion of self.

You've likely heard this idea before, i.e. the illusory self, nonself, nonduality, emptiness, etc. It's an ancient concept. One that has haunted and liberated the most introspective among us for thousands of years.

But like most ancient practices, it's woefully underutilized, under studied, and relegated to the realm of monks.

Fortunately, a resurgence of Buddhism, mindfulness, and meditation has put this illusion back into scope, at just the right time. A time when technology and AI is about to warp our sense of self, including all of its inputs: identity, agency, even free will.

As such, the illusion of self is no longer just a mystical inquiry. It’s a survival skill; a precondition for psychological sovereignty in the age of AI.

This distortion will bring many oddities and risks, some knowable, most not... But fortunately, they all rest on a single assumption: that beneath it all, there’s even a solid “self” to begin with; a persistent 'center' of being in the cross hairs.

This essay will help you challenge this assumption.

It's a collection of ideas, exercises, and experiments to help you not just understand the illusion intellectually, but to feel it experientially, and ultimately, live from the truth and freedom it reveals.

To be clear, I’m no guru. I’m far from an expert on this stuff. I’m just a guy trying to become a better father, friend, and leader. I’m also trying to become a more independent thinker, unmediated by the wants and needs of the outside world. Towards that end, I’ve tried all the things; all the self help books, the plant medicine, and the therapy. Each was useful in its own right. But this is the thing that has grabbed me most. It’s the furthest upstream, hitting the roots of all suffering, and of most all our modern day plights.

In the end, you’ll leave realizing this illusion isn’t just theoretical. It's structural, empirical, and becoming increasingly validated by science. And in an age of infinite avatars, curated identities, and AI companions, it's also becoming a dangerous trap.

Now, I'm far from free of it (hence the reason for this essay). But when I encounter those who are —people who radiate a certain stillness, clarity, and responsiveness—it’s clear that dissolving the illusion doesn’t detach them from life. It roots them more deeply in it. They move through the world with a grace we’re all quietly yearning for. A grace that will be critical in the exponential age.

Because one thing has become certain. This new era will indeed bring abundance. But largely within the material world. Our inner world faces a scarcity of meaning, purpose, and groundedness, largely due to a sense of self that will be maximally malleable, programmable, and monetizable.

The time to start preparing for this future is now. Doing so will involve a seemingly strange but profound set of perspectives and tools, from seeing that you have no head, to not wanting to ever trust your eyes again, to embracing your lack of free will.

So with that, let's begin, starting with a life update that sparked this whole pursuit.

A Wake Up Call

Life just changed in the most meaningful way.

We had a baby girl!

Her name is Chloe and she's a warm, wiggly, cooing bundle of joy, tucked into the pouch of my new 'kangaroo' shirt as I write this essay.

She's also a wake up call; to get out of my head and become more selfless.

No small task... I've always been more self-centered than I care to admit; lost in my inner world and tormented by a tyrannical ego; whipping me incessantly towards a better version; smarter, richer, funnier, more accomplished, more... admired. Psychologist call this 'the idealized self': a mask built not from who we are, but from who we thought we had to be to earn love and escape shame. This result is a collage of childhood pain, cultural ideals, and personal distortion.

Perhaps you know this feeling. It's a constant inner competition with yourself. But win or lose, the result is often the same: tension, guilt, exhaustion, and a burning frustration that these feelings even exist.

In our youth, this tension is useful. It fuels ambition as we carve out a place in the world. But as we get older, it starts to backfire, especially as other 'selves' begin to matter more than just our own; a life partner, a child, an employee. These people need us to show up in a different way.

Yet more often than not, we remain lost in the labyrinth of our own becoming.

Quite the paradox... how the act of becoming becomes the very thing keeping us from who we want to be.

This tension is a tale as old as time. But now, the labyrinth is evolving. Technology is warping it into a black hole. Tiny screens and algorithms fuel the 'act of becoming' on the grandest of scales, in the most profound of ways.

The net effect? We get what we want on demand, but rarely what we 'want to want'.

Philosopher René Girard called this mimetic desire — the idea that we don’t create our own wants/desires, we unconsciously borrow them, copying what others around us seem to want; their ambitions, their preferences, their ideals. More often than not, we don't intrinsically value these things. Our unconscious psyches just see someone else getting love and attention for having them, and decide to pursue the same.

Mimetic desire has always been part of the human condition, but it's inflamed by social media and influencer culture, and now being super charged by AI. Hell, the influencers are becoming AI's, leading us to crave the fullest forms of fabrication.

Needless to say, we're hurdling towards a strange new world, defined by virtual worlds and avatars, AI agents and AI companions, brain computer interfaces and gene editing.

When any person can be a curated projection, and every digital space invites you to perform a new persona, the question of “who am I?” isn't just philosophical— it's practical.

So... who are you? What exactly is this feeling of a self? Here’s my working definition and a target for our inquiry.

Understanding the Self

For most of us, 'the self' is the main character of our story. It's the feeling of 'me' at the center of experience; a fixed entity who thinks, feels, decides, and acts. It's the pilot living in your head, with a personality, wants, dreams, and desires.

This feeling is so intuitive, so innate, that questioning it almost feels absurd. Of course you are you, and I am me, and well... that's just that. End of story.

But modern neuroscience offers a different story. According to cognitive scientist Dan Dennet, our sense of self is just a 'useful fiction', a mere narrative we tell ourselves, about ourselves. And to be fair, it's very useful, indeed. I need to think of myself as a father, a husband, a business partner— if only to make it through the week, much less excel at each.

As such, it's important to clarify: this is not the sense of self worth challenging. What we're targeting is more fundamental and subtle.

It's also the greatest source of suffering. It's the feeling of being a subject internal to our bodies; a mini-you behind your eyes. This version of self — an ego both produced by and identified with thought — is where the burden lies. Fortunately, it's also not a solid, concrete thing. It's a simulation. Or rather, to draw an eerie parallel to our new AI friends, it's a generative model.

Philosopher Thomas Metzinger calls it the Phenomenal Self-Model — a kind of internal avatar your brain assembles to unify experience and track itself in the world. And it works beautifully, stitching sounds, colors, smells, sensations into a coherent tapestry of “subject object"—instead of a random chaos of disconnected inputs. Neuroscientists call this 'sensory integration'.

But—and here’s the uncomfortable part—this model doesn’t reflect reality directly. It constructs it.

Take color: there’s no green “out there” in the world, only light waves bouncing around. Your brain interprets those waves and gives you the ‘feeling’ of greenness—what philosophers call qualia, aka the subjective, felt qualities of experience; the "what it's like" aspects of mental states.

As for the ‘self’, this feeling is what neuroscientist Anil Seth calls a 'controlled hallucination'. And it's entirely convincing because it’s transparent — we don’t see it as a 'model'. We just see it as me. One major reason for this is memory. It convinces us there's a stable 'me' who persists over time.

Now, by this point, some of you might be nodding along. “Sure,” you might say, “I get it. The self is fluid. I’m not the same person I was ten years ago. I’m a socially influenced, ever-changing mix of biology and psychology. I’m fine with that.”

And yes, that’s a perfectly valid view.

But even if you intellectually accept that the self is a construct, notice what still lingers beneath: a quiet but persistent sense of being someone—a distinct “me” behind the experience. A self who has a body and mind, but is somehow separate from both.

This is embedded in our language. In the West, we don’t say “I am a body.” We say, “I have a body.” That subtle phrasing reveals everything.

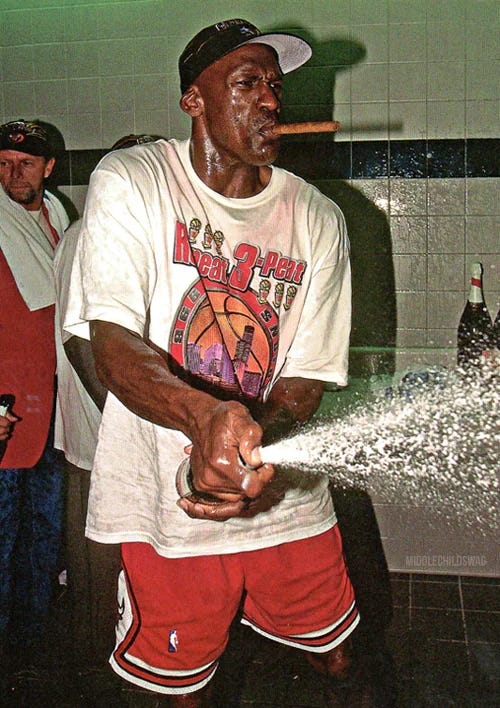

As a quick thought experiment, let's play with our innate capacity for imagination and desire. Close your eyes and imagine being your favorite athlete or super star, say Michael Jordan or Taylor Swift.

How'd that go? Could you imagine having MJ's jump shot and spraying champagne after a championship win? Did you envision a glitzy outfit and blonde curls bouncing in your face while 'shaking it off' in front of 100,000+ screaming fans?

But notice something subtle: you didn't imagine and desire being MJ or T Swift. That wouldn't make much sense. They've already lived those experiences. What you imagined/desired was being you, in their body with their talents.

This tiny twist... this possibility to form such a desire, it shows how we don't identify as a body or mind, but rather, as something beyond... something that has a body/mind, and in principle, could have another one.

This is just one example of many showing how deeply the illusion runs. Its purpose isn’t to argue about the power of imagination, or to prove or disprove the existence of a self. It’s to just highlight how our ability to even form such desires—and to imagine a “me” swapping out bodies like outfits—suggests that, on some deep, automatic level, we believe ourselves to be 'a self'.

And this implicit belief doesn’t stop with imagination. It finds its most enduring home in religion.

Because if we can imagine inhabiting different bodies, it’s not a huge leap to imagine the self surviving the loss of this one altogether.

Across cultures and traditions, the belief in a soul—a self that outlives the body—has been the default setting for most of human history. Whether it travels to heaven, hell, or into another life entirely, the soul is often treated as the real “you,” somehow untouchable by death.

Ancient traditions like Hinduism call in an Ātman — an eternal, unchanging self identical to the divine. This Atman survives bodily death and is central to the cycle of rebirth.

Islam calls it Ruh and Nas. Ruh being the "divine spirit breathed into humans by god". Nas being the sef or ego, portrayed as "the sea of base desires that must be purified".

Christianity evolved this into the immortal soul — the true “you,” distinct from the body, judged by God after death.

So whether through cultural inheritance or cognitive instinct, we tend to experience ourselves as selves. We are wired to believe in a self the same way we are wired to fall for the Müller-Lyer illusion:

Even when we know the lines are equal, they still look unequal.

So, if we hope to see the lines as they are... it helps to ask:

Did we arrive at the idea of the self or soul through a first-principles investigation of reality?

Or did we invent it—because it was socially and emotionally useful? A mere patch to manage fear, morality, mortality?

Also, if this ‘feeling’ of self is just an evolutionary survival strategy, what role does it play in our future? How can this newfound awareness support our next evolutionary leap?

We'll answer all these questions and more in Part II. But if you want to jump ahead, by all means! See this link here → Part II | Future-Proofing Your Self