Future-Proofing Your Self: A Survival Guide for the Age of AI | Part II

The illusion of self and why it matters now

If you’re just joining us, welcome! Great to have you on this mind erasing bending journey. But if you want this essay to fully land, highly suggest starting with Part I → Link to essay here.

In Part I, we defined the 'self' and explored its origins through the lens of science, philosophy and religion.

In Part II, we'll explore ways to see the illusion.

But first, let's align on the core argument here and why this effort matters.

When we say the self is an illusion, we are not denying that we exist.

Rather, we are attacking a very specific instinct — the feeling that there is a separate, unified "me" who owns a body, who owns mental states, and who acts independently (rather than causally) upon the world.

Our ultimate goal is to replace the mistaken idea of 'a self' with a more grounded understanding of what we really are: 'persons'. This idea comes from modern day philosopher and academic, Jay Garfield, via his book, Losing Ourselves.

Garfield defines persons not as pre-existing, independent selves, but as... "dynamic patterns constructed through ongoing relationships and social interactions."

Unlike the illusory “self” that seems to float above our lives, directing things from the outside, a person is more like a song — something that only exists while it's being played.

We emerge from the interplay of biology, culture, language, and experience, not apart from it.

Said another way… Illusions are not about complete non-existence; they involve something existing in one way but appearing in another. A mirage, for instance, is a real pattern of light that might appear to be water.

Likewise, a person exists as a real, socially and biologically embedded being. But it appears to be a separate, autonomous self.

The alternative is recognizing that we exist not as independent selves but as persons: physical beings embedded in networks of causes and conditions, social beings shaped through language and relationships.

We do not pre-exist and then interact with the world; we emerge from it, constructed through our biological bodies, our cultural context, and our interactions with others.

Our inability to grasp this is so natural, so automatic, that entire civilizations have been built upon it. As mentioned in Part I, The Greeks spoke of the "psyche," Christians of the "soul," Indians of the "atman" — all different ways of trying to name the mysterious "me" inside the machine.

But trying to define the self is like trying to measure how deep the water is in a mirage — the thing you’re seeing/feeling isn’t actually there.

The truth is, we aren't isolated pilots. We are more like waves on the ocean — shaped by the winds, tides, and other waves around us.

Like a five-dollar bill, we’re real not because of some intrinsic essence, but because of the roles, meanings, and agreements that give us form. To understand yourself, you don’t need to look within for some hidden core — you need to look around at the web of causes and conditions that make you who you are.

This reminds me of one of my favorite quotes.

"I am not who I think I am. I am not who you think I am. I am, who I think, that you think I am..."

Read that again. Chew on it. It’s this quote that sparked my curiosity on this topic…

And yet… even if this makes sense intellectually, the moment you stop thinking about it, you snap right back into the old operating system. The sense of “I” returns like a reflex.

So how do we stay rooted in this insight? How do we not just understand it — but see it, feel it, live it?

I don’t have the full answer, but I have uncovered a set of ideas, metaphors, and mental models that can help.

And it starts at the beginning, with how we all began... as babies :-)

A newborn truth

I've spent the last couple years wrestling with all the big ideas here, spanning ancient philosophy, cutting-edge neuroscience, zen koans, etc.

And then last month, the clearest clue arrived: our newborn baby, Chloe.

Before language, before memories, before the world teaches us who we are, her experience reveals part of the answer: the self isn’t something we’re born with — it’s something we build.

According to developmental neuroscience, a newborn’s brain hasn’t yet developed the systems needed to separate “me” from “not-me.” Core abilities like proprioception (sensing where your body is), interoception (feeling your internal states), and multi-sensory integration (connecting sight, sound, and touch) are still maturing.

As a result, newborns live in what some scientists call an “undifferentiated soup of sensations.” Their vision is blurry. Their body map is incomplete. They don’t yet feel like a defined someone having experiences — they just are. That’s why one baby’s cry can trigger another’s: the line between self and other hasn’t solidified yet.

Even the brain’s Default Mode Network — the system responsible for self-referential thought and inner narration in adults — is mostly inactive in early infancy. It only begins to come online over months and years, reinforcing the idea that the self is a developed feature, not a built-in one.

Psychologists have long described this early stage as “primary narcissism” or the “oceanic feeling” — where the infant feels no clear separation from the caregiver. When a baby is held or fed, it’s not yet experienced as something done by someone else. It just happens. It’s only through repeated interactions — “when I kick, I see movement,” or “when I cry, someone comes” — that the brain begins to form patterns.

These patterns eventually give rise to a sense of agency and of self.

Milestones like recognizing themselves in a mirror around 18 months mark an early step in this construction, but even that is just the beginning.

This developmental arc aligns perfectly with the understanding that the adult self, despite its convincing feeling of solidity and permanence, is an emergent phenomenon; a "useful fiction" or "controlled hallucination," as Anil Seth suggests.

Newborns are the ultimate proof: they don’t "lose" a self or struggle with its illusions; it simply doesn't exist, yet.

The “I” we hold so dear, the inner center of experience, is gradually assembled through physical interactions, social mirroring, language, and memory.’

In other words, we aren’t born with a self; we learn to hallucinate one.

This might sound startling, yet it's validated by science. The boundaries we perceive between "me" and "not me" are not absolute givens. They're learned constructs, essential for navigating the world but not necessarily reflective of an inherent separation from it.

Why does this recognition matter?

Because it challenges our most fundamental assumptions about identity and liberate us from the confines of a rigidly defined ego.

If the self is a construct, it implies a degree of malleability and a deeper, perhaps forgotten, connection to the world.

Babies are the ultimate reminder that identity isn’t fixed. That we’re more fluid, more connected, more open to change than we think.

Beneath all the stories we tell ourselves, there’s still a trace of that original openness — that quiet, 'newborn truth' we came into the world with. And maybe, just maybe, we can find our way back to it.

Now, if you're like me, this might sound like a bunch of mystical mumbo jumbo — 'connection to the world', 'openness'. It's just all so hand wavey.

What does it really mean?

I used to write this stuff off. Until I stumbled upon something I couldn't deny…

That I have no head.

The Headless Way

If I told you that you have no head, you’d probably look at me like I have two.

I know I know, it sounds ridiculous. But there's a (disturbing) line of inquiry that makes it hard to ignore, if not plausible. It's also one of the more profound ways to think about the illusion of self, and to level set on what we really are…

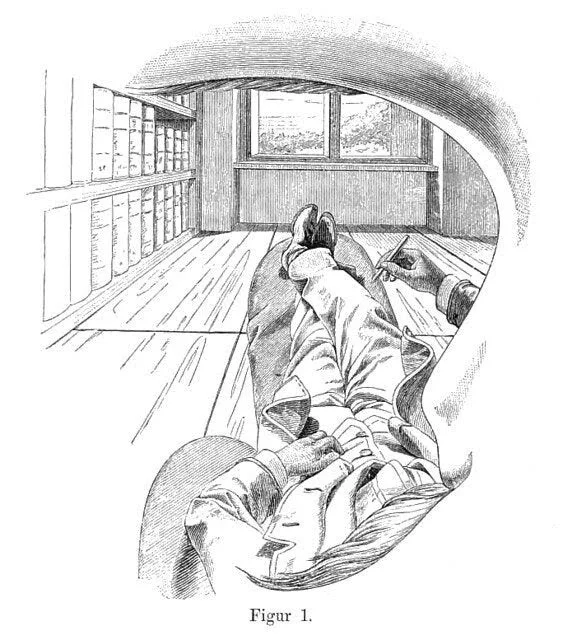

The idea comes from Douglas Harding, a British architect-turned-philosopher who coined the “Headless Way.” His big insight wasn’t born from some ancient manuscript or psychedelic trip — it came during a walk in the Himalayas.

During his trek, he paused, looked down at his body, and then out at the mountains. In that moment something clicked: from his own direct perspective, there was no head. No face. No eyes. Just a wide-open field of vision, containing the world — his legs, the path, the sky, the peaks — but no “thing” doing the seeing.

The “me” he’d assumed lived behind his eyes was experientially absent.

His famous quip was, "I lost a head and gained the world."

What Harding realized is something most of us never question: we assume we’re looking out of a head, but we never actually see that head from our first-person perspective. It’s always inferred — never observed.

In other words... you can see your hands, your legs, your shoes, and the furniture around you. But if you try to see your own face—without using your phone’s camera or a mirror—you can’t. From your own point of view, your face is invisible. It’s just not there.

Rather, you’re just aware of everything in front of you. It’s like you’re a space or an opening through which the world appears. Other people see your face, but you never do directly.

This is difficult to intuit, so Harding created a simple experiment to help people (at least begin) to understand…

First, point at things around you—your shoes, your friends, the wall. You see them clearly.

Next, point back at your own face. What do you see?

Nothing—just the world in front of you.

The idea is that, at the center of your experience, you’re not a person with a head looking out—you’re more like a camera lens or a window: open, clear, and empty, with everything appearing in that space.

It's worth pausing here and letting that sink in…

When I first heard this, it hurt my brain. So here are a few metaphors that helped me understand.

Think about the nature of a window. The window doesn’t see itself; it’s just the opening through which you see everything else.

Similarly, think about a camera. The camera never photographs itself; it just shows what’s in front of it.

Now, consider the sky. It's open and empty, and all the clouds and birds just pass right on through.

Useful, I hope... But Harding wasn’t just being metaphorical.

He insisted this was a literal description of experience. What we see in the mirror is a construct — a few feet away, from another perspective. What others see is a socially agreed-upon “you.” But what you find at (what he called) 'zero distance', from your own center, is not a head looking at the world — it’s an empty space filled with the world.

So, what does this mean?

It means your true “self” isn’t a thing you can see or point to—it’s just an open awareness where all your experiences happen.

It’s a way of seeing yourself that’s very different from how you usually think about being a 'self/me' with a face and a head. Instead, you’re the space where the world shows up.

This 'space' sounds a lot like Garfield's notion of us as 'persons', not selves…

Indeed, Garfield and Harding are saying the same thing, but with different tacks.

Garfield says we're not selves separate from the world, but persons mediated by it and within it.

Harding would say... you are not a thing among other things. You are “No-thing,” and precisely because of that, you are the space in which everything appears.

This might just sound like a fun philosophical trick. But I assure you, as I spend my nights tending to a crying infant, changing diapers in a complete stupor, this has real world implications.

Seeing your “headlessness” disrupts the automatic belief that you are a separate, located ego trapped behind a face. It interrupts the habit of thinking of yourself as an object in the world, and reveals a more immediate, more intimate reality: that your true nature is open, borderless, and deeply connected.

This shift can bring psychological relief, (especially when mid diaper change, you suddenly yourself being both pooped and pee'd on).

You’re no longer a vulnerable little self perched behind the eyes, trying to manage a chaotic world. You are the space in which the chaos appears — and that space is untouched, undisturbed. It’s free.

Harding also noticed how this shift changes relationships.

When you see that you have “no face” here, you become space for the faces of others. Interactions become less confrontational — not face-to-face, but face-to-no-face. You’re more present, more available. Less busy protecting a self-image, more attuned to the world around you.

And the deeper you go, the more freeing it becomes. If the “self” you thought you were isn’t actually here, then what is there to defend? What is there to lose?

Well, for starters: the fear of death, the pressure to perform, the need to constantly assert your identity — all of it starts to loosen its grip.

This is what Harding meant when he said the Headless Way leads to “the peace that passeth all understanding.”

Not because you believe in some abstract truth — but because you looked, and noticed what’s always been right here; no head. No center. No thing. Just this wide, open space — quietly holding the world.

Making this applicable

If this topic interests you, check out Harding's book, On Having No Head. It's an esoteric gem and Harding wielded it for sixty years, trying to convince people to test this claim for themselves.

If only he was alive today... he would have known, this was his theory's moment.

Because that empty center he speaks of... it's the one dimension Silicon Valley can’t hijack.

Sure, algorithms can bend your preferences, curate your desires, and even clone your voice. But they can’t colonize a vacancy.

When you recognize the center as spacious, the latest mimetic frenzy on your feed loses sticking power. There’s no inner Velcro for it to latch onto.

Think of headlessness as a “psychotechnology", i.e. a perceptual trick you can deploy in the checkout line when your toddler erupts, or right before presenting quarterly numbers to a board of caffeinated VCs.

Pop the hood, notice nobody’s driving, and the nervous system resets to factory settings of ease and attentiveness.

To make this more visceral, here are are some personal 'day in the headless life' moments:

It's early morning. Too early... I stumble to the sink, baby monitor crackling on the counter.

Toothbrush in hand, I catch my reflection. A familiar father-face stares back, but here on this side of the glass? Vacancy. The mirror becomes a frame around the scene rather than evidence of a cramped identity.

Chloe wails; sound erupts inside the same openness. I respond, but the response arises unforced, like weather.

Now, the dreaded afternoon Zoom call. Ten rectangles float on the screen, each a curated persona. I toggle gallery view off and drop into headless seeing: colleagues speak; words appear; my own voice joins the mix; nowhere is there a solid epicenter absorbing credit or blame. Ironically, performance improves when there’s no one to impress.

The day's winding down. I'm on an evening stroller walk. Sunset flares across Austin’s sky. In place of “I’m under the sky,” the sentence flips: “Sky, trees, stroller, wife—all appear inside … this.” The boundary between inner and outer crumbles. I'm not zoning out; I'm tasting the scene without the usual packaging.

Objection handling

In closing, let's arm you with some objection handling. Because no doubt, they're going to come, be it from that little voice in your head, or a friend during happy hour.

Here are some of the most common…

“Isn’t this just escapism?” It would make for a strange escapism... given that headlessness drops you more fully into sensations than the normal selfie-centric mode. You’re not transcending life—you’re removing the tinted goggles.

“If there’s no self, who raises the baby or answers the email?” Tasks still get done. The spreadsheet edits itself the same way your heart beats itself. Agency functions, but minus the tight-fisted claimer of agency. It's responsibility without the migraine.

“Sounds cool, but doesn't it fade?” Yes. The default mind springs back like memory foam. Harding recommends dozens of micro-glimpses a day— a finger point, a mirror flip—to erode the reflex. He saw practice not as climbing a ladder toward enlightenment but remembering a joke you keep forgetting to laugh at.

But let's be honest, it's unlikely you'll find time to point at objects and then back at yourself, especially when it might be needed most, in public…

As such, we must go deeper into your programming, and hack it from the inside out.

Doing so starts with realizing the extent to which your mind is already an expert hacker in itself, keeping you from seeing what's actually happening, out there in the 'real' world (all for evolutionary benefit).

We’ll cover all this and more in Part III, by studying some scientific experiments that more empirically lift the veil. But if you want to jump ahead, go for it! Hit this link here → Part III | Future-Proofing Your Self

Brilliant stuff, Evan.