Future-Proofing Your Self: A Survival Guide for the Age of AI | Part III

The illusion of self and why it matters now

Welcome back to our series on the illusory self.

In Part I, we defined the 'Self' and explored its origins.

In Part II, we explained the illusion and how to grasp it (by studying babies and realizing you 'have no head').

Here in Part III, we're taking a more empirical approach. It will make you question… well, just about everything.

If you haven't read Part I & II, highly recommend doing so, else this essay might not land 🙂

But I get it. Time is money and money is time, so here's an all-too-short recap: the self you think you are, that pilot behind your eyes, isn't what you think it is.

It's not a persistent, stable entity (e.g. a soul, an independent 'you' that exists across time & space). It's just a feeling, produced by a sophisticated model—weaving sensory data, memories, and social feedback into what feels like a coherent, persistent self.

Said another way... while the self is real as an experience, it is illusory as an actual object (in both our internal/external worlds). It's just evolution's biological user interface—helping a body navigate complexity without being crushed by it.

My favorite explanation comes from cognitive scientist Donald Hoffman, and his book The Case Against Reality.

Hoffman argues that evolution has not shaped us to see the truth, but to see what helps us stay alive and pass on genes.

His analogy is striking (if not a bit disturbing): all of reality is like a desktop interface. The icons on your screen don’t reveal what’s actually happening inside the computer—they give you a simplified, usable illusion.

The self is just one of those icons. It’s not real in the way it appears—but it helps you navigate the game.

This can be hard to believe. It implies our (internal & external) perceptions are some sort of lie. But as this essay reveals, at a fundamental level, that's exactly what they are. Lies. Or at the very least, white lies…

The Empirical Truth

Indeed, your brain hides the truth. It does not deliver raw data about the world. What feels like a live broadcast is really just a post-production, editorial suite (and sorry... but you aren't the editor).

I’ll explain with the most basic of games: a race.

Races don't start with a flashing light, they start with the crack of a gun.

But why? Light travels much faster than sound. Isn't it a better signal?

Nope.

Light travels faster but it takes longer to process through the neural cortex. In fact, all of our senses are on their own schedule; they hit our brains at different times, through different channels. Yet somehow, they seem in sync…

Neuroscientist, David Eagelman, has done multiple experiments on this front, revealing how our brain sorts and times our senses.

The first experiment is simple. Participants press a button and then see a light flash on a screen.

They continue to do so, but what they don't realize is that Eagleman is introducing a slight delay each time. Just 10 milliseconds at first. Then 20ms. Then 30ms, all the way up to a 200ms delay in the real world.

But as this happens, their brains don't perceive the delay. They re-adjust. Their brain tells itself, "I've done something and I should get something visual back, so let’s just adapt to this delay".

After a while, their brain gets used to it. But then suddenly, Eagleman removes the delay.

This time, when they hit the button they’re jostled with surprise.

The system glitched. They see the light flash before they fully press the button. As if the effect had caused the cause.

But that's not what happened. It didn't glitch, they did. In the physical world, the light went off as it should: after they pressed the button.

So what's behind this sensory flip?

Something called postdiction, i.e. your brain's tendency to finalize reality a moment after an event.

It quickly gathers recent sensory data, then retroactively constructs the most coherent story. Expecting a delay between a button press and a flash, its removal caused the brain's internal model to misfire, making the flash seem to precede the press.

This is not a bug in the brain—it’s a feature. The brain had rewritten its expectations and adapted to the altered world. When that world snapped back, it didn’t re-adapt fast enough.

Instead, it created an illusory reversal of cause and effect.

This illusion doesn't just happen with vision. It also happens with sound, touch, and even intentionality.

Indeed, we've found a rip in the Matrix; a window into how our brains construct reality—not as a live stream, but as a best-guess reconstruction, edited after the fact for narrative coherence.

More simply stated: your brain isn’t showing you the world as it is. It’s showing you a version of the world it thinks makes sense. And that feeling of "you" as a coherent self—acting with free will, in real time—is part of the constructed story.

The crazy part is that this is all by design. Evolution didn’t care about showing you the truth—it cared about keeping you alive. A coherent sense of self, like a coherent perception of a flash, is a useful shortcut. It helps you navigate the world without drowning in sensory chaos. But it’s not reality. It’s fiction.

And this shows how far your brain will go to keep the story consistent— even if it means bending the truth.

This brings us to perhaps the most dramatic evidence of your brain’s narrative prowess: studies of people whose brains have been split in half…

One Skull, Two Selves

These editing tricks don’t stop with vision. The same narrative machinery shapes your sense of self, agency, and free will.

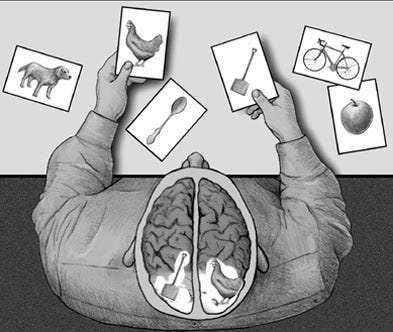

No experiment reveals this more clearly than the famous split-brain studies.

In the 1960s, neuroscientists studied patients who had undergone a rare surgery to treat severe epilepsy: cutting the corpus callosum, the thick neural bridge connecting the brain’s two hemispheres. As a result, two brain halves are now unable to communicate.

You’d expect total dysfunction. But strangely, these patients seemed fine. They could walk, talk, and go about life as if nothing had changed.

Until researchers looked closer.

They devised an experiment to send visual input to just one hemisphere at a time. The right hemisphere (which can’t speak but controls the left hand) was shown a snowy scene. The left hemisphere (which controls speech and the right hand) was shown a chicken claw.

Then came a test: the patient was asked to point to related images. The left hand picked a shovel (to clear snow). The right hand picked a chicken (for the claw).

When asked to explain both choices, only the left hemisphere could respond—and it had no idea the right hemisphere had seen snow.

You'd expect the patient to say something like, "Well, I picked the chicken because I saw a chicken claw, but I have no idea why my left hand chose a shovel."

Instead, the patient’s left hemisphere confidently said: “The claw goes with the chicken, and the shovel is to clean out the chicken shed.”

A complete fiction—but told with total confidence.

This is the brain’s default move. When it lacks information, it doesn’t stall or admit confusion—it fills in the blanks. Not to deceive, but to preserve the feeling that everything is part of one smooth, intentional, (you guessed it) story.

Neuroscientist Michael Gazzaniga, who led many of these studies, called this built-in narrator “the interpreter.” It’s like your brain’s PR agent—always spinning a narrative, even when it has no direct knowledge of the events. It values coherence over truth. Narrative over facts.

And this need for unity runs deep. In other split-brain experiments, the two hands—controlled by different hemispheres—actually fought. One hand would reach for a shirt, the other would swat it away. One hand would start a task, the other would try to stop it.

Two minds in one body, in complete disagreement. Talk about internal conflict…

All of this underpins our initial thesis: there’s no single self in charge. The “you” you feel is the interpreter’s creation—a tidy story woven from messy, distributed processes (or multiple ‘selves’).

This brings our journey full circle. Just as newborns reveal the self as a learned construct, and the Headless Way shows no solid "you" at the center of experience, split-brain experiments deliver our final blow to the myth of a single, indivisible self.

Your brain can operate like a divided government with multiple selves running in parallel, and the "I" you think governs it all is just one part of the system—often the last to know what's going on.

Which raises an even deeper question: if the self is a story, who—or what—is the author?

We'll explore this question and more in Part IV... stay tuned. Or, if you want to jump ahead, by all means. Hit this link here → Part IV | Future-Proofing Your Self.