As robots and embodied AI move from the lab to the real world, a new discipline is emerging: RobotOps.

This is not just MLOps applied to robots.

It’s an entirely new discipline for running systems that move through the physical world all day, every day.

For the non-technical: MLOps is how dev teams reliably train, deploy, and operate machine learning models at scale.

It was built for the internet and it assumes AI lives in a safe, predictable digital bubble; where nothing can explode and data changes slowly.

If something breaks, it’s usually a math problem, not a physics problem; you just check the dashboard, teach the AI model a new trick, and push a software update.

Over the last decade, we’ve perfected the assembly line for this, with standard tools to organize data, track experiments, and manage versions, all optimized for things like chatbots, Netflix movie recommendations, and spam filters.

These systems live safely behind an API in the cloud, far away from the chaos of reality.

Physical AI breaks those assumptions, creating an entirely different paradigm.

The difference begins with what is being operated.

In MLOps, the primary artifacts are models, datasets, features, and training code.

Data is typically tabular, textual, or image-based, collected passively from digital systems. Models are trained offline, evaluated against static benchmarks, and deployed into well-instrumented digital environments.

In RobotOps, the artifacts are far more interdependent and dynamic: perception and control models, sensor configurations, calibration parameters, 2D/3D maps and world representations, simulation environments, digital assets, and massive streams of multimodal sensor data captured during real-world operation.

Code and models still matter, but they are no longer the center of gravity. Behavior, data, and interactive environments are.

The feedback loop also differs.

MLOps closes the loop through metrics, predictions, and downstream business signals inside digital systems. This includes:

Click-through rates (did the model’s prediction cause a user to take the intended action?)

Classification accuracy (how many predictions are technically “correct”)

Drift statistics (is the data is slowly changing?)

Loss curves (is a certain math score during training is going up or down?).

From there, data is logged, analyzed, and fed back into retraining pipelines on a human-defined cadence.

In contrast, RobotOps closes the loop through the physical world itself.

A deployed model produces behavior; that behavior interacts with an unpredictable environment; sensors capture the consequences; and those sensor logs must be ingested, indexed, graded, and transformed into new training data and simulation scenarios.

This loop is continuous, not episodic.

Training, validation, and operations collapse into a single, always-on learning system (or at least, that’s the goal...)

Failure also carries a very different weight.

In traditional MLOps, a failure is annoying: a model becomes biased, a user sees the wrong ad, an irrelevant search result is surfaced.

In RobotOps, failure is physical. It means damaged hardware, safety incidents, regulatory nightmares, or the silent poisoning of future training data.

A bad model doesn’t just output a wrong number; it creates a dangerous event.

Because of this, RobotOps has to treat provenance (knowing exactly where data came from) and determinism as survival mechanisms, not just best practices.

Knowing exactly which model, environment, and scenario caused a robot to twitch isn’t a debugging convenience. It’s a safety requirement.

And then, we have the most fickle of beasts: simulation.

This is where the gap between MLOps and RobotOps becomes a canyon.

In MLOps, you look backward.

You validate models by replaying historical data or shadow-deploying alongside existing systems. The model sits safely behind an API, observing the world without touching it.

In RobotOps, you must look forward.

You can’t just ask how a model performs on past data; you have to ask how it behaves when the world pushes back.

To answer that, you need simulation. You need to run candidate models through thousands of procedural scenarios (rare edge cases, lighting changes, sudden obstacles) before you ever let code touch a physical machine.

But here is the hard truth about simulation today: For most teams, it’s a pipe dream.

Ignore the shiny visuals you see in keynote demos. While a handful of advanced, deeply funded companies have achieved full-fidelity digital twins, the reality for the other 95% is starkly different.

Building a photorealistic, physics-accurate virtual world isn’t just an engineering task; it effectively requires building an in-house AAA game studio.

Today, most teams use simulation sparingly, mostly for synthetic data augmentation or simple component testing. It lives on the periphery.

Over the next few years, this will invert.

Eventually, simulation will move from a supporting role to the center of the development loop, becoming the primary environment for validation, regression, and learning.

But first, some core challenges must be addressed, starting with simulation’s fragility; if one small piece breaks, the entire run fails, so you can’t easily retry or patch part of the job like you would with normal ML training.

On top of that, you have massive 3D asset dependencies; each run depends on huge 3D worlds, physics models, and 3D models, and if you can’t replay thousands of simulations in exactly the same way every time, you can’t trust the results or compare models reliably.

The next MLOps vs. RobotOps contrast is automation.

MLOps automation is largely pipeline-driven and rule-based. Humans decide what data to collect, when to retrain, how to evaluate models, and which versions to promote. Automation accelerates execution, but intent remains human-defined. For now...

In RobotOps, the complexity quickly exceeds what humans can manage manually. Deciding which data is missing, which edge cases matter, which scenarios to simulate next, and which models should evolve becomes an ongoing cognitive bottleneck.

This is where AI-native automation enters the equation, and might be necessary to achieve serious scale.

I’m already seeing early signals of this: vision-language models auto-labeling sensor data, world models grading synthetic scenario quality, and agents proposing new simulation campaigns based on observed failures.

Over time, these agents will operate entire segments of the learning loop autonomously.

This is the true inflection point: when RobotOps systems begin to improve themselves faster than humans could ever direct.

To be clear, existing MLOps tools like model registries, training pipelines, orchestration frameworks, etc... these things still matter. But they operate at too low a level.

RobotOps requires higher-order abstractions: scenarios instead of datasets, behaviors instead of predictions, simulation campaigns instead of experiments, data grading instead of drift detection, and learning loops instead of deployment cycles.

In this sense, RobotOps is not just the next evolution of MLOps. It is the operational layer for embodied intelligence: systems that learn through action, adapt through experience, and operate under physical constraints.

But before this can be true... we must remove a ton of pain at every stage of the data lifecycle.

Other wise, we’ll never reach the RobotOps holy grail: a fully automated, physical AI data flywheel.

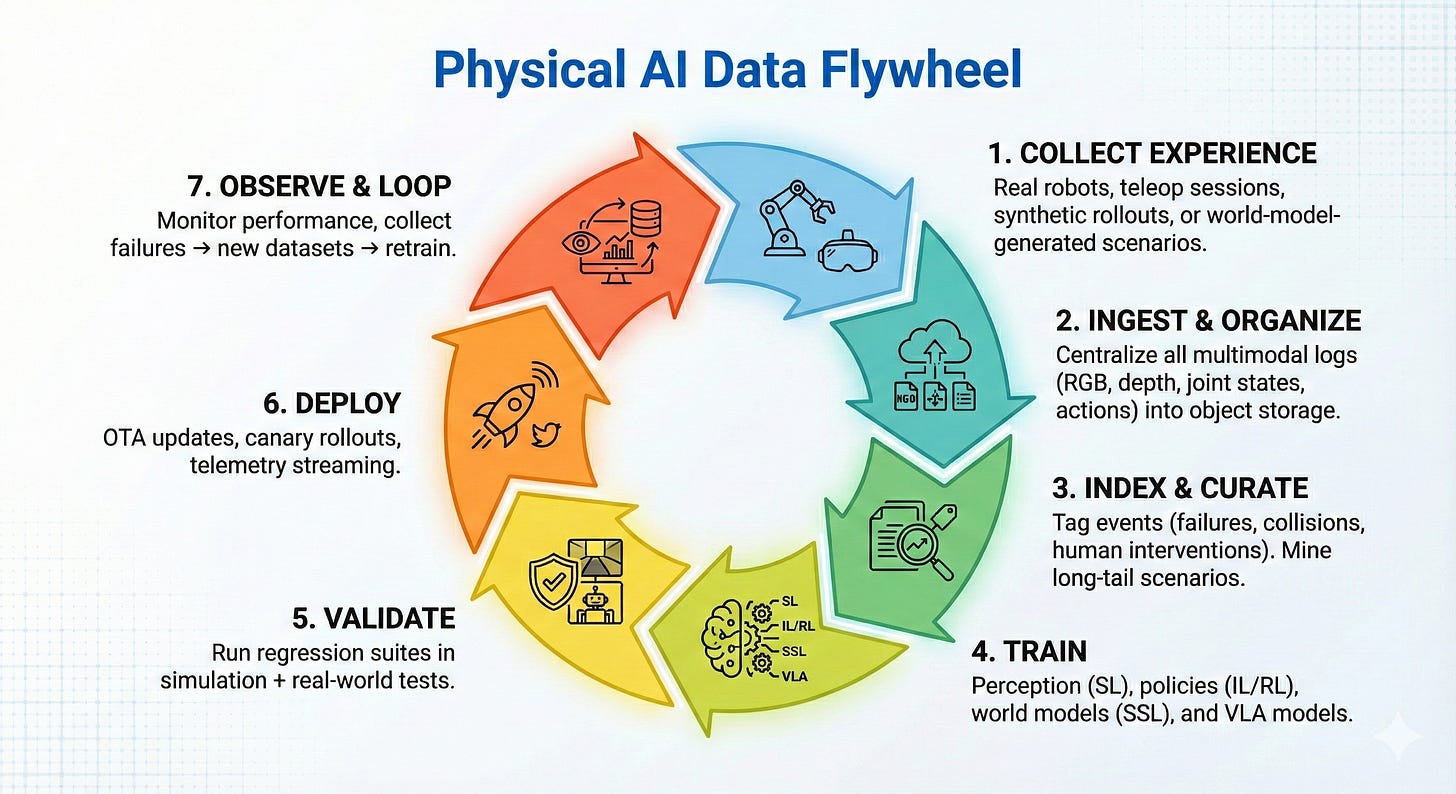

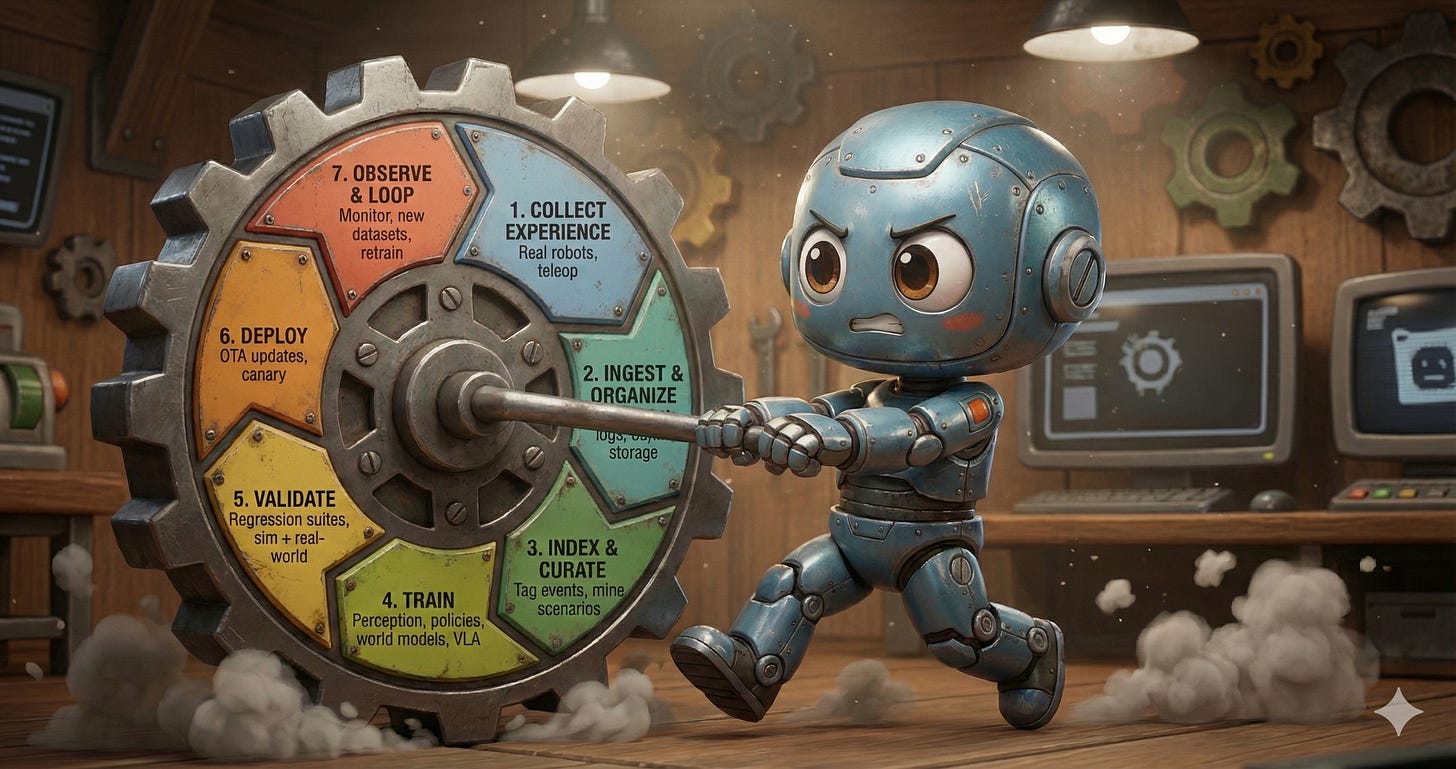

The Physical AI Data Flywheel

Every company has their own version of such a flywheel. Most look something like this.

To really feel that pain, let’s walk through a typical ‘day in the life’ of a robotics developer.

Her name is Maya.

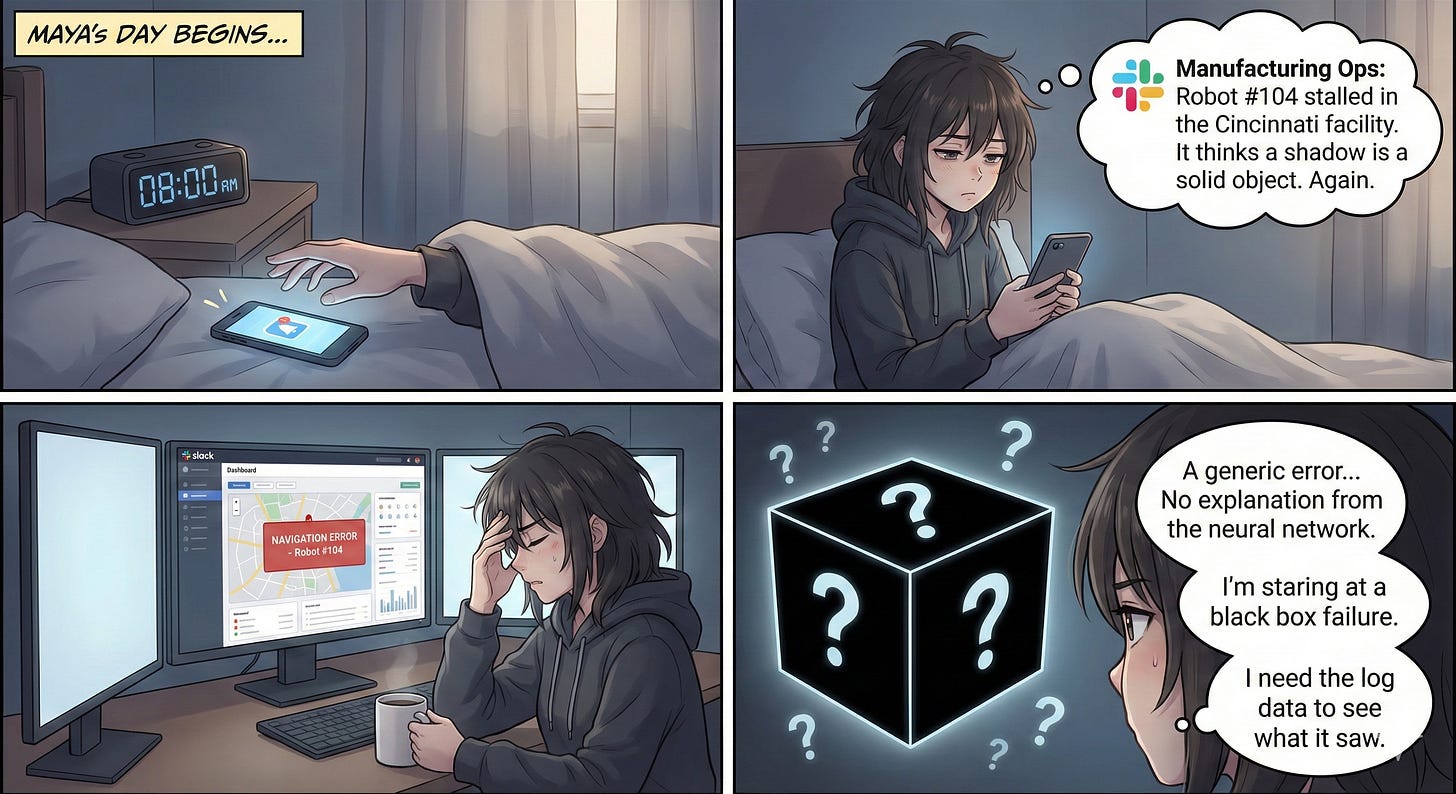

08:00 AM - The Wake-Up Call (Observe + Collect)

Maya’s day doesn’t start with code; it starts with a Slack notification from the manufacturing ops team:

“Robot #104 stalled in the Cincinnati facility. It thinks a shadow is a solid object. Again.”

This moment straddles phases 7 & 1: Observe + Collect Experience.

The robot failed in the real world, but Maya has no idea why. The dashboard shows a generic Navigation Error, but the neural network offers no explanation. She is staring at a black box failure. To fix it, she needs to see what the robot saw— she needs the log data.

The underlying challenge: Robots fail silently, and observability is shallow

In robotics, most failures are not clean crashes. They’re subtle misinterpretations of the world: shadows, glare, dust, vibrations.

Yet most fleet monitoring systems surface only coarse error codes, not the perceptual or decision context that caused the failure.

Unlike traditional software, where logs explain behavior, neural policies often provide no causal trace. The “observe” loop exists, but it’s thin: teams know that something failed, not why.

This makes learning reactive, slow, and highly manual.

09:30 AM - The Sneakernet Struggle (Ingest & Organize)

Maya tries to pull the logs from Robot #104 remotely, but she hits the ingest bottleneck immediately.

The robot is deep inside a concrete warehouse with spotty Wi-Fi. It has generated 500GB of LiDAR and camera data in the last shift alone, but the upload speed is crawling at 2MB/s.

She can’t wait three days for the upload. She let’s out a deep sigh and calls the site manager in Cincinnati. He answers and she quickly makes her ask.

“I need you to physically walk out to the unit, pull the SSD drive, and upload it from the main office fiber line,” she says.

In an era of 5G and Starlink, Maya is still relying on the “Sneakernet”, physically moving drives because the bandwidth cost of streaming terabytes of raw sensor data is simply too high.

She is forced to make a blind decision: drop 90% of the data to save bandwidth, hoping she doesn’t accidentally delete the one frame that captures the failure.

The underlying challenge: Physical data is heavy, remote, and bandwidth-constrained

Robotics data is fundamentally different from web or mobile data. High-resolution video, LiDAR point clouds, and dense telemetry quickly reach terabyte scale. And robots often operate in warehouses, factories, fields, or mines with poor connectivity.

As a result, data collection becomes opportunistic and lossy. Teams must choose what not to upload before they know what matters. This breaks the data flywheel at its foundation: learning systems depend on complete context, but physical constraints force premature filtering.

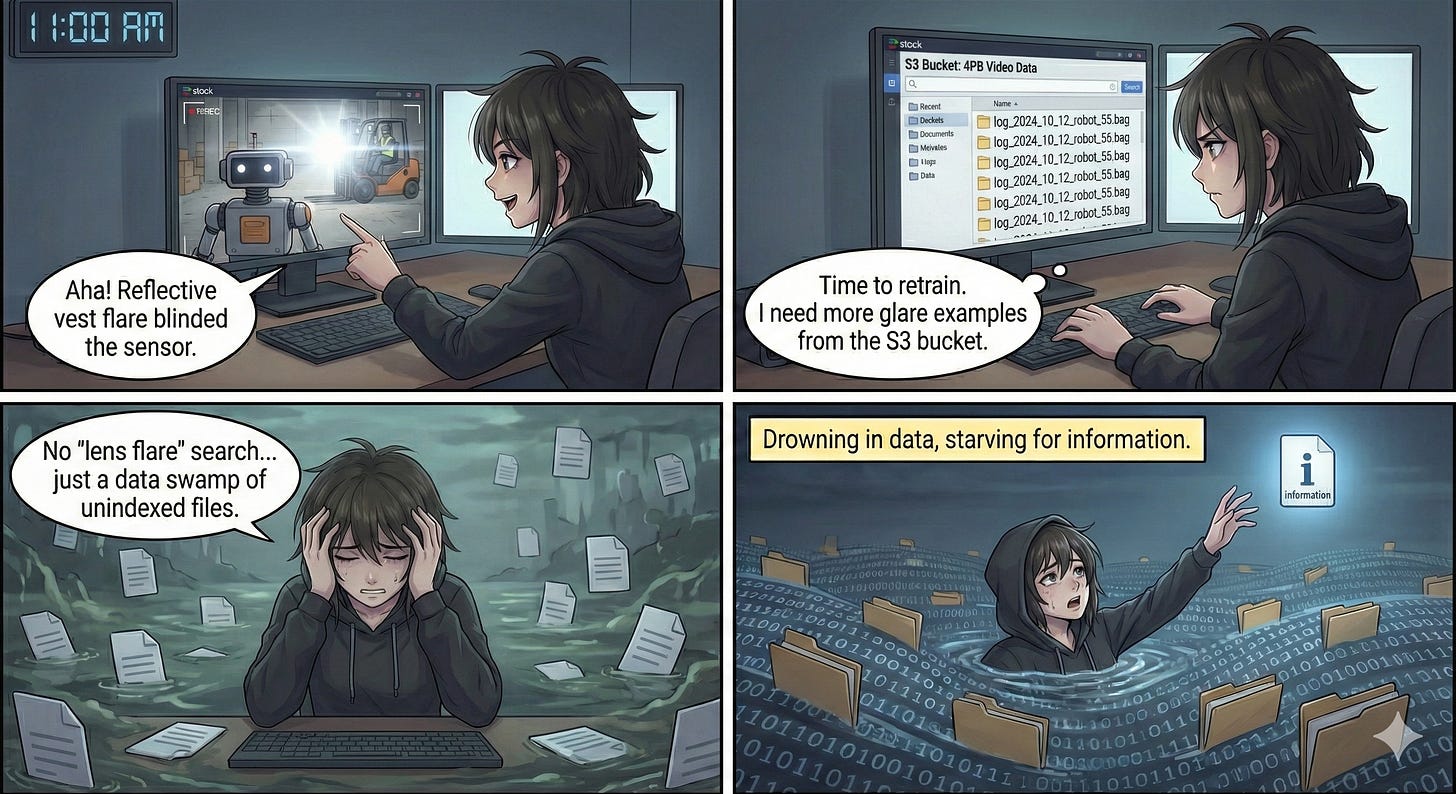

11:00 AM - The Needle in the Haystack (Index & Curate)

The logs finally arrive. Now Maya faces the data curation nightmare.

She watches the replay: a forklift drove by with a reflective safety vest that flared in the camera lens, blinding the robot’s depth sensor.

She knows exactly how to fix this: retrain the vision model on more examples of high-glare reflections.

She opens her company’s S3 bucket, which holds 4 petabytes of video data from the last two years. But it’s a data swamp.

The files are named things like:

“log_2024_10_12_robot_55.bag”.

There is no search bar. She cannot type: “Show me videos with lens flare.”

Instead, she spends the next three hours manually scripting queries and skimming through random videos, hoping to find boring footage of shiny objects.

She finds 200 hours of useless driving for every 10 seconds of relevant glare.

She is drowning in data, but starving for information

The underlying challenge: Robotics data is often unindexed, unlabeled, and semantically blind.

Robotics teams collect massive volumes of data, but lack tools to search it by what happened, not when it was recorded. Failures are semantic—glare, hesitation, near-miss—but storage systems only understand filenames and timestamps.

Labeling is manual and expensive, so the most valuable edge cases stay buried. The real tax on iteration speed isn’t data collection—it’s curation.

The root cause is structural. Robotics data lives in formats like ROS bags or MCAP—black boxes that contain everything, perfectly synchronized. But once stored in the cloud, they become opaque blobs. A system can see a 50GB file, but not what’s inside. Container formats solve storage, not understanding. So teams build fragile pipelines and scripts just to find a single failure—turning weeks into days, and learning into archaeology.

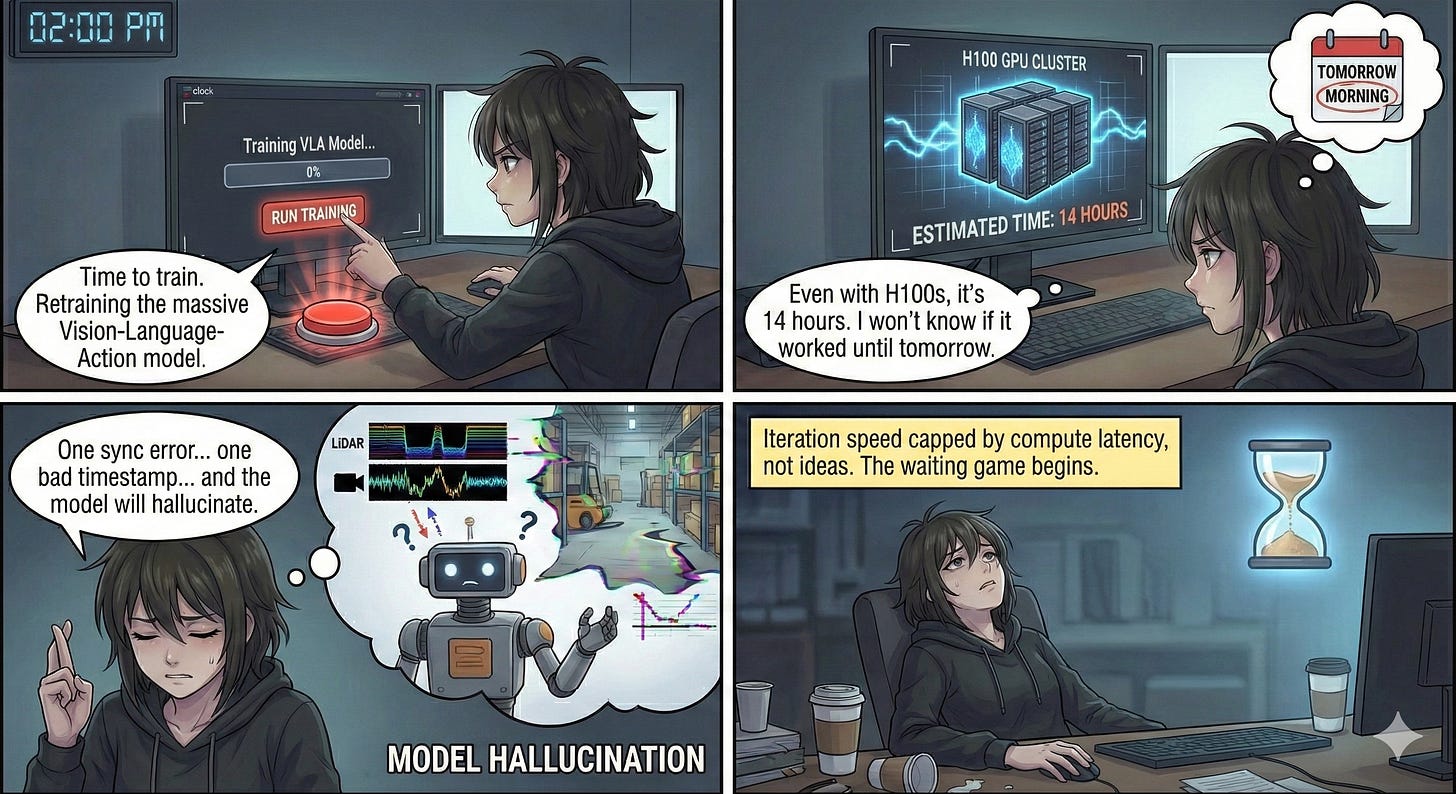

02:00 PM - The Waiting Game (Train)

After painfully assembling a small dataset of “shiny vest” scenarios, Maya kicks off a new training run. This is the training bottleneck.

She is retraining a massive Vision-Language-Action model. Even with a cluster of H100 GPUs, this will take 14 hours. If she made a mistake in the data formatting — if even one timestamp is out of sync between LiDAR and camera — the model will hallucinate, and she won’t know until tomorrow morning.

She hits Run and crosses her fingers, knowing that her iteration speed is capped not by ideas, but by compute latency.

The underlying challenge: Training is fragile, slow, and tightly coupled to data quality

Modern robotics models are compute-hungry and extremely sensitive to data alignment.

A single synchronization bug can invalidate an entire training run, wasting hours or days of GPU time. Unlike web ML pipelines, robotics training must reconcile multiple sensor streams, action spaces, and temporal dependencies.

As models grow larger, iteration speed collapses; not because engineers lack insight, but because feedback loops stretch across days instead of minutes.

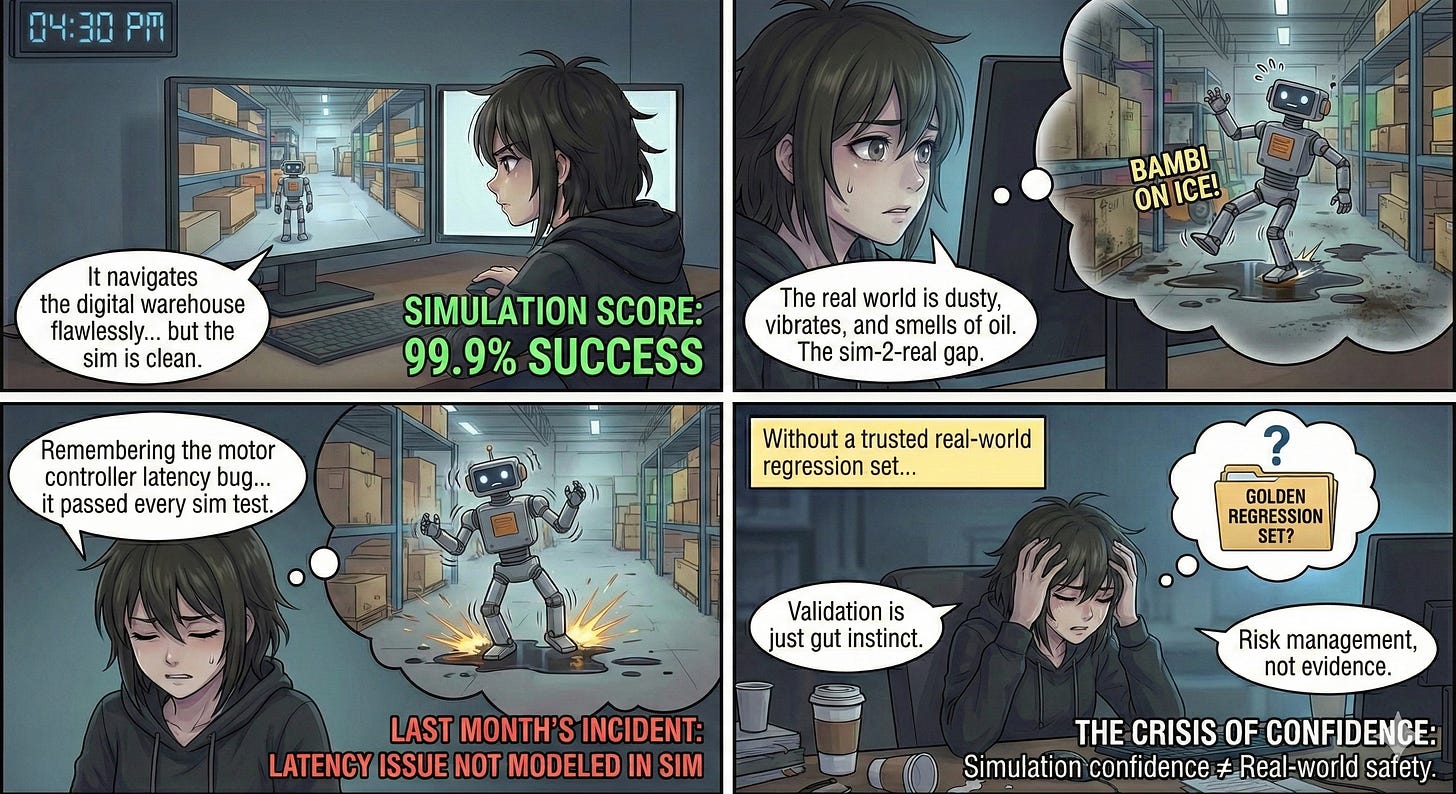

04:30 PM - The Crisis of Confidence (Validate)

While the model trains, Maya reviews a candidate model from the night before. It’s time for validation.

In a 3D simulation, the model scores 99.9% success. It navigates the digital warehouse flawlessly. But Maya feels the familiar sim-2-real anxiety, aka the sim-2-real gap.

The simulator is clean; the real world is dusty, vibrates, and smells faintly of oil. Alas, the occasional oil spill, aka robots doing their best ‘Bambi on ice’ impression.

(insert Bambi on ice image)

Maya remembers last month’s incident: a model that passed every sim test but caused robots to oscillate violently because the simulator didn’t model the latency of new motor controllers.

Without a trusted “golden regression set” of real-world scenarios, validation becomes less about proof and more about gut instinct.

The underlying challenge: Simulation confidence does not equal real-world safety

Robotics validation lives in an uncomfortable gray zone. On one hand, simulation is necessary but incomplete. On the other, real-world testing is slow, expensive, and risky.

Most teams lack standardized, trusted regression suites grounded in historical failures.

As a result, validation becomes subjective—an exercise in risk management rather than evidence. This uncertainty compounds as fleets grow, making every deployment decision emotionally and organizationally heavy.

06:00 PM - The Button Press (Deploy)

It’s time to push the patch. This is the deploy fear.

Unlike a web developer who can roll back a bad update in seconds, Maya is shipping code to a 300-pound machine moving near & around humans.

A bug here isn’t a broken UI, it’s a collision or worse.

She initiates a canary rollout, pushing the update to three robots in a low-risk zone (Canary rollout = deploying to only one or two robots to ensure everything’s working properly)

Maya will watch them obsessively for the next 24 hours. The fear of bricking hardware or causing harm slows everything down.

The team could deploy daily, but because of the risk, they deploy monthly.

The underlying challenge: Deployment carries physical, reputational, and regulatory risk

Robotics deployment is software delivery with real-world consequences.

Rollouts must be staged, monitored, and reversible—but many teams lack mature tooling for fine-grained canaries, fleet segmentation, and automated rollback.

Each deployment becomes a high-stakes event, encouraging conservatism. The result is a slow, cautious flywheel where learning is throttled by fear rather than ambition.

The Cycle Continues

Maya leaves work. The model is still training. The canary robots are still running. Tomorrow morning, she’ll open Slack to see whether the flywheel spun forward, or whether a new edge case brought it grinding to a halt again.

The meta-challenge: The flywheel exists, but it doesn’t compound

In theory, robotics should improve continuously: failures generate data, data trains models, models improve behavior.

In practice, each step is fragmented, manual, and fragile. The loop turns, but slowly, unevenly, and with enormous human effort.

Until the data flywheel becomes automatic, semantic, and tightly integrated end-to-end, robotics progress will continue to feel heroic rather than inevitable.

With that... Stay tuned for Part III.

We’ll be re-examining a day in Maya’s life, but this time, in the not-too-distant future; in which these challenges are solved, the fly wheel is automated, and human-robot collaboration is the norm.

We’ll also dive deeper into simulation, and all its fun challenges, traps, and promise.

So if that interests you, be sure to subscribe! More to come on the future of physical AI and being human out on this wild new frontier.

Oh, and in case you missed Part I of this series, here’s the link:

Physical AI Deep Dive: Part I | Market Timing

It answers the ‘why now’ question for physical AI + robotics.

The answer in a sentence: breakthroughs in data collection, vision language action models, and training recipes, i.e. bespoke combos of SL + RL/simulation + IL.

Otherwise... until next time!

Absolutely brilliant breakdown of the infra bottlenck here. The Maya example really hammers home how much time gets burned on data curation instead of actual model improvements. I've seen similiar patterns in manufacturing where teams build bespoke Python scripts for every edge case, and then wonder why their feedback loops are so slow. The insight about RobotOps needing to look forward rather than backward is spot on, especially when validation becomes more gut check than evidence.

It's interesting how you break down the real complexities here. This distinction between MLOps and RobotOps is so crucaial for understanding physical AI deployment. You always manage to articulate these new paradigms so clearly. It realy makes you think about the future of automation. Spot on!